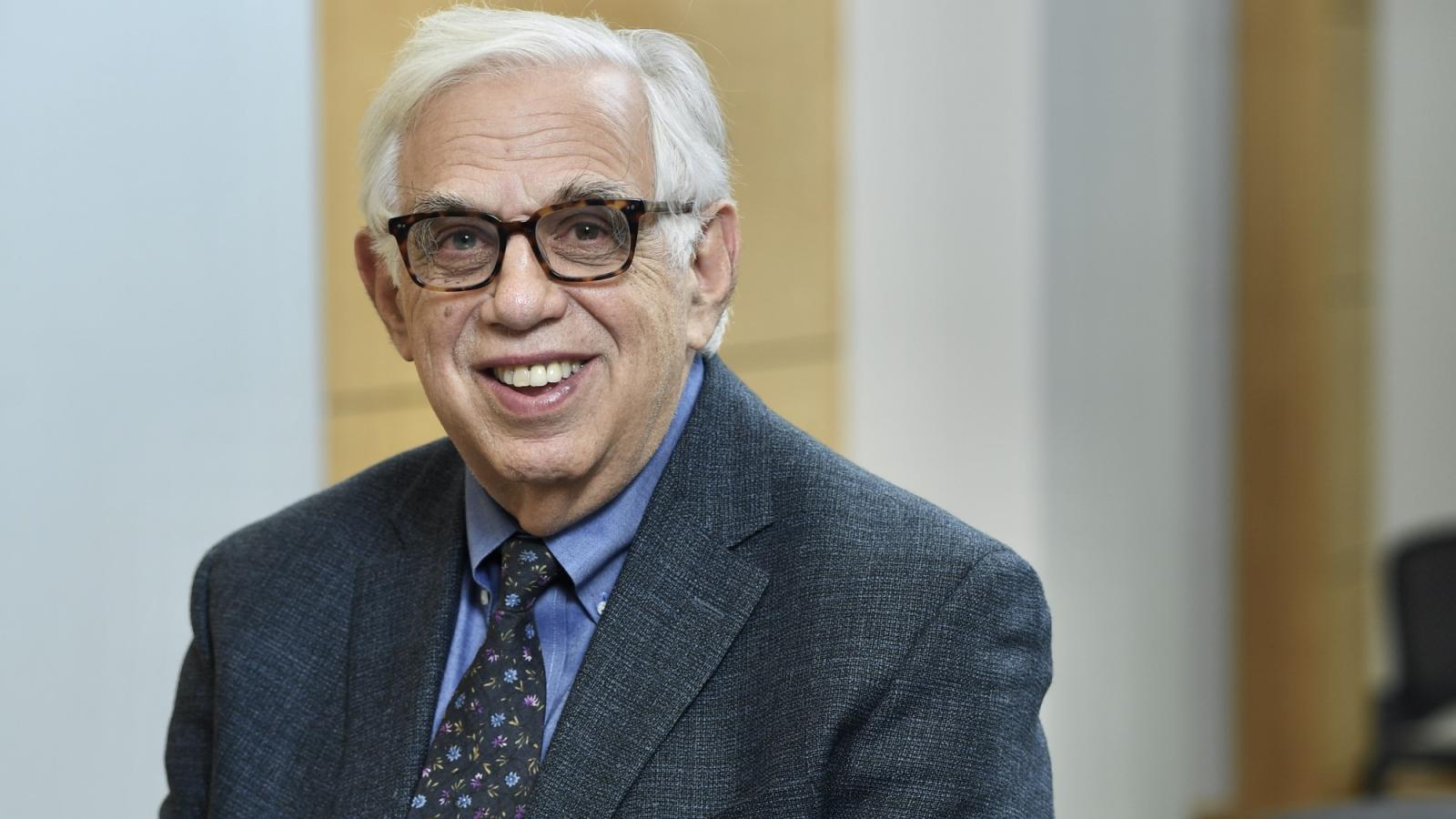

Faculty Focus: Professor Michael B. Mushlin

Professor Michael B. Mushlin has been a professor at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University (then known as “Pace Law School”) since 1984. He teaches Civil Procedure, Criminal Procedure Adjudication, Evidence, Federal Courts, and Prisoners’ Rights. After growing up in the south, and witnessing firsthand racism in America, Professor Mushlin decided to go to law school. Today, Professor Mushlin is a preeminent authority on prisoners’ rights, the author of the treatise, Rights of Prisoners, and a beloved professor. Learn more about him in this candid Q&A.

You are always involved in interesting and timely matters - what has some of your more recent work involved?

I appeared as an expert witness in an extradition case in Scotland involving an American woman who is wanted for murder in the United States. I testified about the lack of oversight of the penal institutions to which the defendant would be sent in the United States were she to be extradited. I also testified about the risk of solitary confinement and the threat of COVID-19. I also serve of the New York State Advisory Committee on Criminal Law and Procedure where I chair the subcommittee on judicial visits to prisons. I recently wrote an op-ed for the NY Daily News on the maltreatment of prisoners, and a letter to the Editor of the NY Times on Rikers Island as well as op eds in the Westchester County Bar Association Magazine and the New York Law Journal. I plan to give a lecture soon to the Pace University community on originalism and prisoners’ rights and will be speaking at a national conference on prisoners’ rights at the University of Texas.

How did you become interested in Prisoners’ Rights?

After growing up in the deep south and seeing firsthand, from the perspective of a white person, racism in America, I went to law school to become a civil rights attorney. After I graduated law school, I began my legal career as a staff attorney at a neighborhood legal services office in Harlem. Afterwards, I went to work for the Legal Aid Society as staff attorney and then Project Director of the Prisoners’ Rights Project where I served for seven years. My passion and interest in the area grew from there. I used the lessons learned doing prisoners’ rights litigation in my work as Associate Director of the ACLU’s Children’s Rights Project.

What advice do you have for students interested in the law and in particular, Prisoners’ Rights?

The first step is to make sure that you understand what being a lawyer is like and that this is what you enjoy and want to be good at. As far as prisoners’ rights, I would highly recommend taking the prisoners’ rights course.

What do you think is today’s greatest issue facing prisoners’ rights?

Americans are fundamentally humane and decent. However, because of fear and the failure to confront the full implications of all aspects of our past we have a prison system that does not reflect these basic values. The biggest issue facing prisoners’ rights is finding a way to establish a connection between the prisons of this country and these American values. When that happens, our prisons will be transformed.

You have written about the damage that solitary confinement in prison causes, and last year, you gave testimony in support of a bill reforming solitary confinement in Connecticut - briefly, can you talk about that topic?

Plain and simple, solitary confinement is torture. It runs against human nature, is painful beyond measure to anyone who experiences it, and violates international law when it is used for 15 days or more. Reforming solitary confinement will not be easy, but it must be done.

How has COVID-19 affected prisoners’ rights?

Here is what I said about Covid-19 when I added a chapter to my book Rights of Prisoners (5th ed) after the pandemic hit:

“COVID-19 poses a greater threat to inmates than it does to people in the general civilian population. Prisons are closed, often crowded institutions. Social distancing in such places is difficult, if not impossible. Normal measures used to stem the spread of the virus, such as cleaning supplies and masks, are not readily available in prisons and jails. In fact, these items are often considered contraband, which inmates are punished for possessing. In addition, inmates are generally not a healthy group of people. Within prison walls, there are many people who have conditions, such as hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, asthma, and obesity, which makes them especially vulnerable to serious injury or death if they contract COVID-19. As is well-known, increasing age is also associated with mortality from COVID-19. In recent years, prisons have become places in which large numbers of older persons are held. For these reasons, it is clear that “[p]risons are powder kegs for infection and have allowed the COVID-19 virus to spread with uncommon and frightening speed (citing United States v. Salvagno)”

What is the most rewarding part of being a professor for you?

I love teaching. The classroom is a sacred space. It is where ideas are engaged, skills that last a lifetime are developed and people grow.

"I love teaching. The classroom is a sacred space. It is where ideas are engaged, skills that last a lifetime are developed and people grow."

What are some of your non-academic interests?

I love to spend time with my wife, my two sons, and my granddaughter. I also have fun with Skip, my 17 year old cockapoo dog who is an adored member of our family.