We're reaffirming our commitment to cutting-edge academics, moving up in the rankings, earning grants, and paying it forward. All this and more in the latest edition of 10 Things to Inspire You.

How the Pandemic Has Changed Talent Management

Since March 2020, our workforce has undergone a number of dramatic short-and-long-term shifts; ranging from the sudden, necessary move to remote work, to larger questions surrounding work-life balance and the overall relationship between employers and talent.

Lubin Professor and Management and Management Science Chair Ibraiz Tarique, PhD, is well-positioned to tackle many of these vital questions. He is an expert on global talent management, (the science behind developing and maintaining a team of high potentials, A-players, Stars and top-notch professional contributors), and is the author of several textbooks, including Contemporary Talent Management: A Research Companion, and The Routledge Companion to Talent Management.

We sat down—or rather fittingly, chatted over Zoom—with Professor Tarique to discuss the emerging field of talent management, workplace changes accelerated by pandemic, and what work might look like in our (hopefully) post-COVID future.

Broadly speaking, what is talent management?

Talent management is a relatively new field, which has different meanings to different organizations. It’s a continuum with two extremes. One is what we call the exclusive approach to talent management, which is when you focus on a small group of high potential employees, stars and A-players, and employees that are more valuable in their performance—what they bring to the organizations. On the other side, there is the inclusive perspective, where the argument is that everyone is talented, and should be managed based on the skill set they have. That in turn becomes HR, and some people have argued that talent management is a new term for human resource management.

My philosophy, and the way I teach talent management, is that it’s a subset of human resource management that focuses on your most valuable employees. The argument is based on the exclusive approach—that is talent should be managed according to his/her contribution to the organization and that there is a small group of highly valuable employees in key or strategic positions that differentially contribute to organizational success. Similar to Pareto’s Principle or the 20/80 rule, where 20% of the employees bring 80% of the revenue or profit.

What impact has the COVID-19 pandemic had on talent management?

Like most other things in human resource management, the use of technology and mobility really impacted how we manage people and how work is done. I think there are important takeaways post-COVID:

- Through technology and remote work, talent is geographically dispersed. Before, you would bring talent to work, now you can take work to talent. If you want talent that is in a different country or location, you now can, through technology, take work to that person, develop that person, and retain that person. This trend was there for a while, but COVID accelerated this trend.

- It’s my observation that employees have more control over their work now—how they work and where they work. If you’re a high potential employee or high performer, you’re controlling the conversation. You’re dictating the terms. Employers are now listening.

- Organizational culture. There has been a discussion going on—Harvard Business Review has had a lot of articles around this—the question of, what is organizational culture now? Culture had been people together in meetings, in the same buildings—but if that’s disappearing, the organizational culture is changing and evolving. We still do not know what the new culture looks like. It’s evolving.

Talent analytics will play a larger role. Everything is being measured all of the time. The question is, what do we do with this data? Real-time decisions will be increasingly made on data.

What are some ways that companies and can adapt to these radical shifts in the way work is done and talent is managed?

From a company perspective, there’s now a focus on virtual leadership. We are moving from a traditional leadership model, to virtual and hybrid. How do you develop virtual leaders? And who will be able to manage and engage a geographically dispersed workforce and talent through technology?

From an academic perspective, we’re developing new content. We’re thinking about how to manage and lead people who you’re not meeting and observing behaviors throughout the day—because one aspect connected to that is also the issue of performance management.

Traditionally, performance management has had two components: results and behaviors. Now with remote and virtual work, observing workplace behaviors is challenging. Whether that’s negative or positive is debatable, but there is a lot of focus on results. But focusing on “results” takes personality and other individual traits out of the equation. When I teach performance management, I mention something called the likeability factor—meaning, sometimes people get away with lackluster results because they’re likeable. But in a virtual setting, this likeability factor can disappear and outcomes, or results, become extremely important. Perhaps this is a good trend.

Over the past year, there have been a lot of headlines surrounding labor shortages and “The Great Resignation.” Can you discuss these trends from a talent management perspective?

The data is extremely new, but we’ve had talent shortages for a long time. There is no shortage of research on “talent shortages”. During the 2008 recession, unemployment was high, yet companies were still saying that they couldn’t find talent. The talent shortage is there all the time, one of the disconnects there is how fast jobs are changing and how quickly people can learn and develop.

What the pandemic did was move people indoors and remotely to work, and a lot of social and psychological aspects came in. Working remotely has caused a lot of stress and burnout—people end up working more and questioning the meaning of their work. Most homes are not designed for working from home. Most families are not used to spending so much time together. People need space, more specifically Gen Y and Gen Z.

For talent management, it means that for any organization, retention is critical and retaining talent becomes a key strategy. In my book, I argue you must customize careers for the current employees. You have to pay attention to each employee to see how the company can help them learn, develop, and grow. I challenge the traditional philosophy of “what can you do for your employer” to “what can your employer do for you?” When you have that conversation as an employer, you might ask: how can we help you move forward in your career? When you start the conversation from that angle, people get motivated, engaged, committed, and eventually stay.

Succession planning is also very important. There is this myth that people have to stay with companies for a long period of time. Turnover is part of life. People will leave. Some jobs, Wall Street jobs for example, could have short-time windows. The key for both the employer and talent, is how to maximize returns within those the short time periods.

For any organization, retention is critical and retaining talent becomes a key strategy.

What do you envision the future of work to look like in the next five years or so?

COVID accelerated the change of hybrid work. You will see more remote work, depending on the jobs. The question regarding having your top talent working remotely will be different—companies will figure out ways to retain talent that is not physically near them.

Talent analytics will play a larger role. Everything is being measured all of the time. The question is, what do we do with this data? Real-time decisions will be increasingly made on data.

Additionally, we have allowed companies to come into our homes, through technology. The work-life balance line between privacy is blurring. Companies are going to play this different role in people’s lives, organizations will have to become like a family member in some way. Connected to that is this increased focus on employee health and well-being—that will continue.

Having said that, I still believe the traditional model will hold. People will come back to work, because the social need for connection will supersede work needs. And for some work, you just have to be in close contact. Secondly, as I mentioned earlier, the home is not designed for working. Our society is no structured that way—which can lead to mental and emotional issues, which eventually will come back to the company.

The answer, like many things, lies somewhere in the middle.

More from Pace

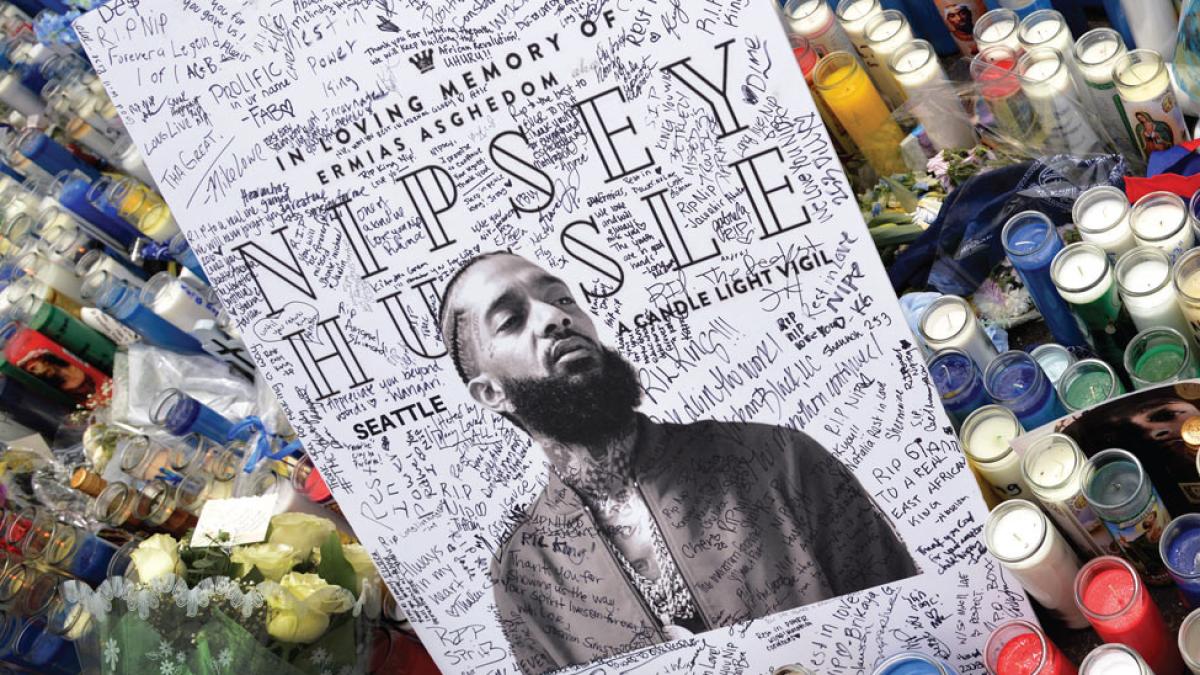

Researchers at Pace dive deep into hip hop’s emotional undercurrents.

Title IX is best known for transforming collegiate athletics in the United States—and, from there, all of sports. But that was not its original goal. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, as it is formally known, was designed to open doors for women across higher education. Learn more about it.