When Research Gets Personal: Meet Pace’s Epilepsy Advocates

It was 2018. Married couple Timothy Myers, PhD, and Kimberly “Kimmi” Stephens, PhD, were settling into their seats at a movie theater to watch The Incredibles 2 for Tim’s birthday.

They didn’t finish the film. During the title sequence, Kimmi had a seizure. She had never had one before, but as a computational and cellular/molecular neuroscientist specializing in an area called network hyperexcitability, he recognized the signs immediately.

He knew it was a seizure, but he didn’t know what to do.

Kimmi’s seizure not only marked a significant shift in their personal lives, but also in the trajectory of their careers, bridging the gap between Tim’s theoretical studies with the stark reality of what it’s like to live with epilepsy.

Tim and Kimmi

Kimmi and Tim met in 2014 at UC Riverside, when Kimmi invited Tim to a Thanksgiving potluck with the Biology Department. Tim was pursuing his PhD in neuroscience, and Kimmi her PhD in entomology. A year later, in December 2015, they married.

Kimmi’s academic expertise is vast, encompassing a wide range of fields including vector biology, host pathogen interactions, reproductive physiology, and circadian rhythms. Her passion for research provided her with an extensive background in protein biochemistry and molecular genetics. She finished her PhD in 2016 while Tim continued work on his degree.

It was kind of ironic that I was a specialist in the field by the time 2018 came along. —Tim Myers

Since 2014, Tim’s research narrowed in on understanding seizure disorders and the process by which the brain develops epilepsy. “I specifically look at the cellular and molecular mechanisms of epilepsy, so trying to figure out what makes certain types of epilepsy start,” Tim explains. “It was kind of ironic that I was a specialist in the field by the time 2018 came along.”

Neither of them knew how much his research would eventually intertwine with their personal experiences.

The Accident

Six months before that day in the movie theater, Kimmi was in an accident where she was struck by a raised Ford F-150. “The car was going about 50 miles per hour, and she flew and hit her head on the asphalt about 40 feet from where she was struck,” Tim recounts. Her survival probability was estimated at 20 percent. Her physical injuries included a compression fracture of her upper cervical vertebra, multiple lacerations, contusions, concussion, loss of consciousness, and severe traumatic brain injury.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. “While Kimmi was in the ambulance leaving the scene, she got a call from our escrow agent saying we closed on our house in Southern California,” Tim said, thrusting the couple into severe financial strain.

But it wasn’t just financial pain, but deep, physical pain that plagued Kimmi. “She has two types of neuropathies, which involves damage to peripheral nerves.” Tim explains. “One is occipital neuralgia, and the other is something called trigeminal neuralgia.” Additionally, Kimmi developed postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) a condition where standing up causes an unusually large increase in heart rate, leading to symptoms including: dizziness, fatigue, loss of muscle tonicity and, in her case, syncope—loss of consciousness.

So profound is the pain caused by this type of nerve damage that it has earned an ominous name. “It’s not a diagnostic name,” Tim says. “But trigeminal neuralgia is called ‘the suicide disease’ because a significant number of people who develop this pain attempt to commit suicide … and Kimmi has both trigeminal AND occipital neuralgia.” Even the American Association of Neurological Surgeons indicates that trigeminal neuralgia is “sometimes described as the most excruciating pain known to humanity.”

This pain went untreated for years.

For years Kimmi dealt with this excruciating pain. —Tim

While there is some relief for the occipital neuralgia via monthly injections directly into the damaged nerve, there is very little that can be done for trigeminal neuralgia aside from invasive surgery. “For the longest time, nobody would give her any medication or help with any therapeutic efforts (with respect to pain management and the seizures) because they just thought she was faking it,” Tim recounts. “For years Kimmi dealt with this excruciating pain. I wasn't even aware of how bad it was because she was so good at hiding it. And she would just walk through life smiling, having conversations with people.”

And then six months later, she had her first seizure in that movie theater. Her form of occipital epilepsy can be challenging to detect and diagnose correctly through conventional electroencephalography—the gold standard of epilepsy diagnosis. Following her epilepsy diagnosis, Kimmi started the next new (and somewhat ironic) chapter in her life post-injury.

The Unbreakable Kimmi Stephens

“I'm going to share something that I know Kimmi hates,” Tim says. “Kimmi is a genius. In third grade, she tested into college level English and math.”

Tim recounts how Kimmi not only turned down an invitation from Mensa, the world’s oldest high-IQ society, but also a full ride to the University of Oxford. Tim marveled at her ability to remember huge amounts of information with ease. “If she had to go grocery shopping for a hundred items, she didn’t even bring a list.” He’d be amazed when they returned home and not a single item had been forgotten.

Then came the car accident, and then the seizure that completely transformed Kimmi’s life.

It had gotten to the point where I basically wasn't doing anything on my own, because of the fear of a seizure. —Kimmi Stephens

She and Tim jokingly recount her hesitation about getting married because she had always been fiercely independent and feared losing any sense of her autonomy. Not only was she set back by the pain and process of healing from a traumatic brain injury, but the epilepsy diagnosis usurped her independent spirit with fear and anxiety.

“It was actually pretty bad,” Kimmi admits. “Because it had gotten to the point where I basically wasn't doing anything on my own, because of the fear of a seizure. If I'm cooking and I have seizure, I’ll get burnt, or pass out and have a severe injury. I was terrified to be on my own. And it's not a healthy dynamic, because I have to be able to do stuff on my own. For me, it's been really hard, not just accepting help, but the fact that I require the help at some points.”

A New World

But life needed to continue. Kimmi was finally prescribed the proper dosage of her antiepileptic medication in early 2019 which facilitated the healing process.

Kimmi came out of a brain fog in mid-2019, Tim insisted that Kimmi find a fulfilling job that she wanted to do, anything, anywhere. He told her, “We'll drop everything in California, I don't care where it is. We'll just start over.”

Kimmi accepted a postdoctoral research position at Mount Sinai School of Medicine focused on developing a treatment for genetic disorders. And so, they packed their bags and moved across the country. Kimmi moved to New York City in early January 2020, where she hoped to reclaim some of the independence she had lost. The couple agreed she’d go alone at first in the hopes that she could establish herself and foster her independence for a few months in the city. However, neither of them could anticipate the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic just a month later. The shutdown kept them apart for nearly a year, leaving Kimmi to navigate all of her disabilities, a new city, work as essential personnel at a major NYC hospital in the middle of a pandemic, and life without accessible familial support.

I have all this knowledge, but I didn't know what to do.—Tim

When Tim finally arrived in NYC, he took a part-time job teaching neuroscience at Columbia University. It was in this role that he decided to inject epilepsy awareness into his classes, because even with his background there was so much for him to learn.

“When Kimmi had her first seizure, I recognized it for what it was, but I had no idea what to do,” he says. “It was the most frightening and humbling experience of my life. I have all this knowledge, but I didn't know what to do.”

Tim finished his PhD in 2021 after leaving his graduate program in 2018 to care for Kimmi and work multiple jobs for better insurance and financial security. “I'm really, really proud of him for finishing his PhD,” Kimmi says. “It was sort of traumatic, because his PhD research was on epilepsy, and then I developed epilepsy. Then he had to go back and look at the research and there's trauma there.”

In the Classroom

Tim’s teaching began to focus not just on understanding the neuroscience behind brain pathologies, but the real world impact for people living with it.

“I realized that my teaching was very static. I'm going to teach you about all this neuroscience, about Alzheimer's, about epilepsy,” Tim says. “But there was no humanistic component to it, which was not something I cared about in the past. But all of a sudden, I realized there is so much value there.”

He and Kimmi formed a relationship with Epilepsy Foundation of Metropolitan New York (EFMNY), whose parent company provides online seizure first-aid and recognition training. When he began teaching neurobiology at Pace during the Spring 2022 semester, he brought this work with him, and now all of his Pace students get certified in seizure recognition and first aid as part of their coursework.

I talk about the mechanisms, what's going on inside the human brain, and then she talks about what it's like to live with these conditions.—Tim

Tim continued to stay mindful of how the impact of his work affected Kimmi. “There’s a fine line in my brain between exploiting Kimmi’s condition and teaching people about her condition,” he explains. So, it seemed a natural progression when Tim asked Kimmi to come and speak to his students in her own words, and she began sharing her experiences with his Pace and Columbia students. Tim thought it would not only be beneficial for his students to get exposure to someone impacted by the issues they were studying in the classroom, but hopefully provide some catharsis for Kimmi.

“I'm not going speak for Kimmi about how it affected her, but personally I've seen her able to open up more and more,” he says. “And the students, particularly the female students, seem to have really positive feedback, because Kimmi doesn't only talk about her experiences with epilepsy, but her wider experiences as a female scientist.”

Tim thinks this personal element is key to teaching their students. “I talk about the mechanisms, what's going on inside the human brain, and then she talks about what it's like to live with these conditions. And I think that's probably one of the most powerful things that we've done for the students.”

In the Lab

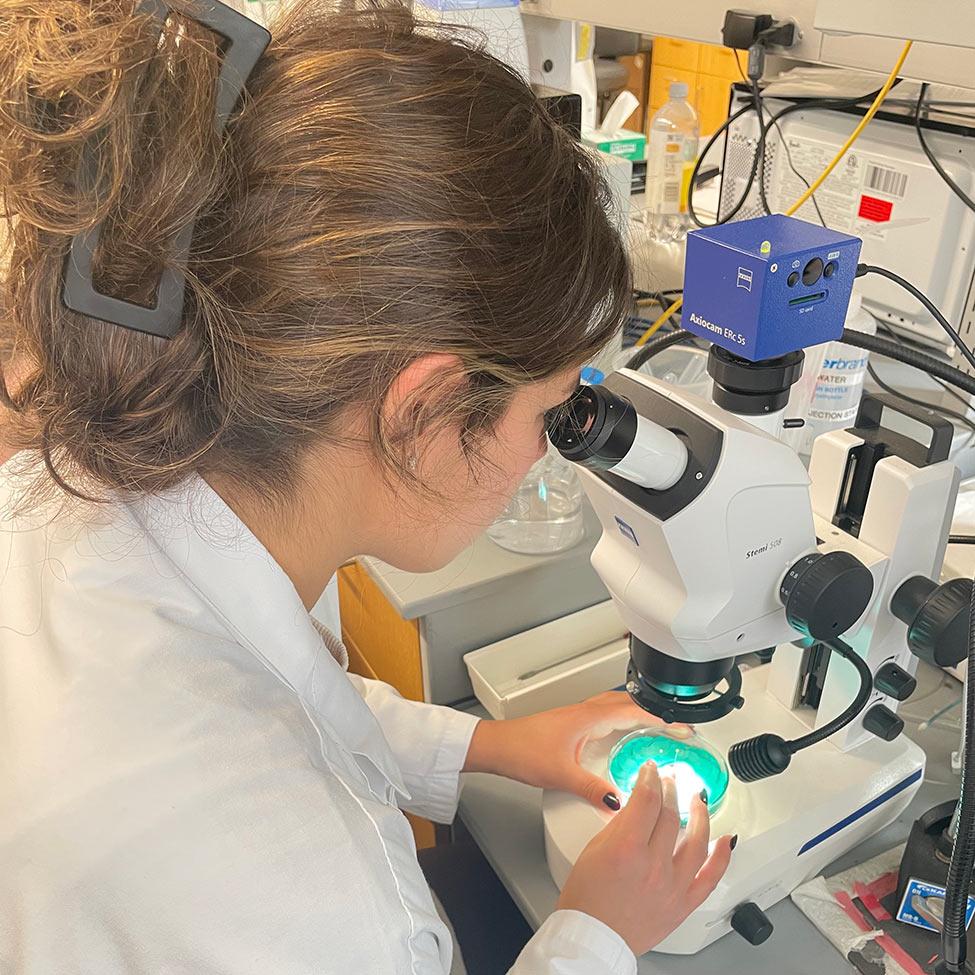

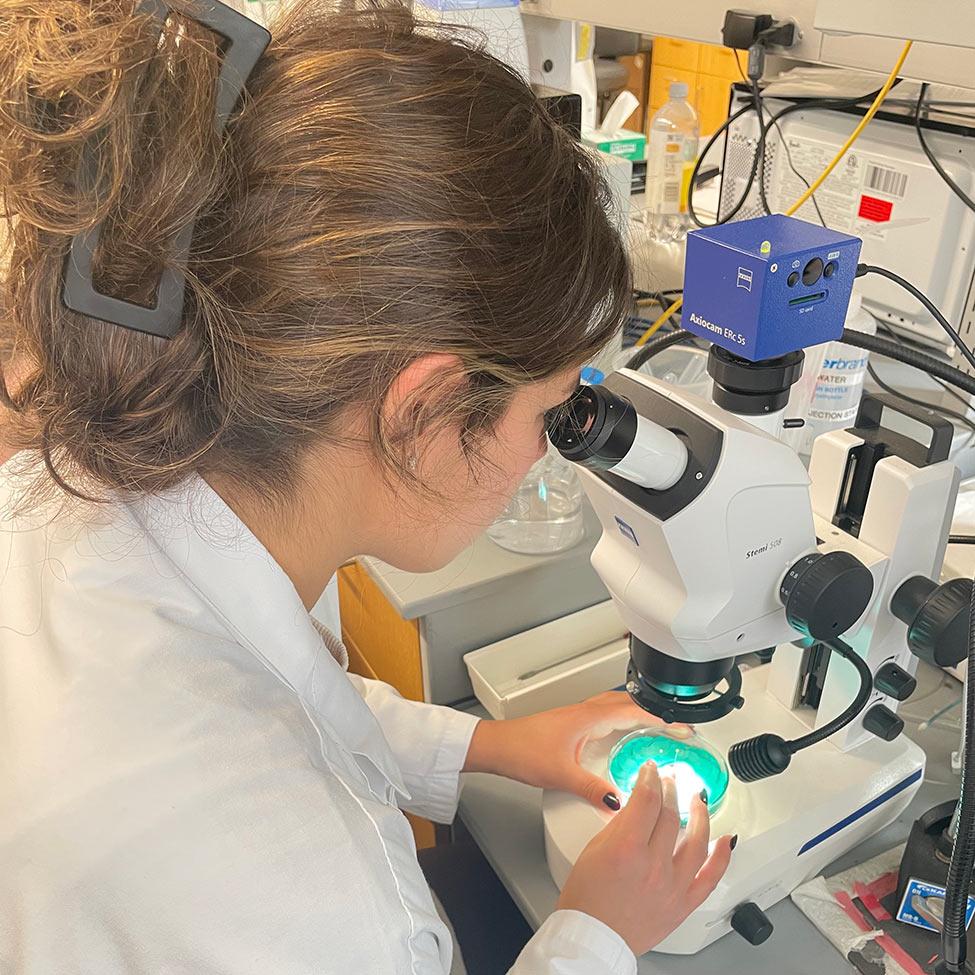

Tim and Kimmi’s work is not just confined to the classroom, though. After completing her post-doctorate, Kimmi came to work at Pace as an adjunct professor beginning the 2023 fall semester. In early 2023, Kimmi officially joined the lab on Pace’s Pleasantville Campus to further develop a comprehensive, and much-needed seizure and traumatic brain injury research program with Kimmi supplying her background on molecular biology and Tim bringing his experience as an electrophysiologist and computational neuroscientist.

Their initial research goal is to examine proteins in the brain linked to the neuroinflammatory response following traumatic brain injury to determine how that might induce seizure activity.

“We jointly decided to take this direction, to conduct research in the area of Kimmi's pathology,” Tim explains. “We hope to increase understanding of epilepsy and potentially contribute to future pharmaceutical interventions.”

Their students have the opportunity to collaboratively explore this epilepsy research. “We currently have three Pace students that have joined the lab this year,” Tim says. Tim developed a computational model of specific proteins and cell interactions within the traumatized brain. In the lab, the students (alongside Tim and Kimmi) will be able to interact and assist in the development of this model, simulating changes in these proteins to observe ‘seizure’ activity within the in silico (computer simulated) environment.

There is also some research equipment at Pleasantville that you wouldn't necessarily find at a smaller university.—Tim

They hope to soon receive approval to expand the lab’s research into the ‘wet lab’ (experiments that use a physical specimen) in which they can study seizure activity in zebrafish. Aaron Steiner, PhD, manages the zebrafish facility on the Pleasantville Campus and utilizes these animals in his research. “Aaron’s expertise, advice and mentorship with respect to fish research has been invaluable,” says Tim. “There is also some research equipment at Pleasantville that you wouldn't necessarily find at a smaller university.”

Their plan is to try to secure more funding, working with organizations such as the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the Epilepsy Research Program (ERP) through the Department of Defense. Aside from reagent and general lab expenses, their hope for this funding is to compensate Kimmi for her lab work (which she currently conducts on a volunteer basis) and to expand the scope of their research into the hereditary nature of hyperexcitability and explore the delay between a TBI and the manifestation of epilepsy—projects which would necessitate the use of zebrafish. They also hope to be able to continue their advocacy efforts and bring epilepsy awareness to a larger audience.

These students have never had a person sort of open up to them like that—Tim

They both express the joy they have at not only finding a home for their lab at Pace—where state-of-the-art lab facilities and collaboration across disciplines has enabled further research—but in the opportunity to mentor these students, from offering their insights into navigating the science field, writing recommendations, and even assisting with PhD applications.

Kimmi has found that she especially has an impact on female students. “I think this is because she talks about what it’s like to be a female scientist, and shares harassment that she’s experienced,” Tim suggests. “These students have never had a person sort of open up to them like that, and just be willing to talk about things that are often considered taboo.”

Teaching the Human Impact

Neither Tim nor Kimmi anticipated how much their life would change after Kimmi’s accident. Their research in the lab and advocacy in the classroom was not something they set out to do but was a natural progression of their work adapting to new challenges. According to Tim, “We were just kind of doing what we think is right. It's what we have to do for our own sanity.”

What they’ve discovered is that while they’re doing work within their fields, they are now equipped to bring something to their science students that is so often missed: the human element.

Kimmi explains, “A lot of our students want to study these conditions or be in the medical profession. I think knowing or interacting with someone with this condition in a less professional situation allows them to actually see the human behind it. In which case, when they go in, they start doing work in these fields, they have a little more compassion for the people that they're treating.”

I think knowing or interacting with someone with this condition in a less professional situation allows them to actually see the human behind it.—Kimmi

Some of their students even experienced the harsh reality Tim had to face that day in the movie theater on a day where Kimmi came to speak as a guest. As she was answering a student question about what she remembered from her accident, she had an absence seizure, which involves a sudden and often brief lapse of consciousness. “It literally happened while she was talking upfront, and everybody got concerned,” Tim recounts. But he was able to remind his students, “I said, ‘Look, you guys are trained in epilepsy recognition and first aid. You’re okay.’”

When Kimmi came to, it was a powerful moment for the students as she reassured them that she chose to come in and speak, and that this is part of her disability. Kimmi admits she has some anxiety about speaking in front of people, and she has the added worry that she could have a seizure at any point. But as both Tim and Kimmi pointed out, the lack of awareness has created stigmas around disabilities, and about what people with disabilities are capable of. Especially, as Kimmi points out, in the sciences.

“Science, in particular, can be a little bit toxic,” she says. “They push people to be super productive to the point that a lot of people don't really get a chance to relax or take care of themselves.” For her, she has the added worry that her epilepsy and POTS might cause people to doubt her abilities.

I think it's really important that they see and hear the human aspect of it.—Kimmi

But Kimmi, despite her anxiety, and despite her seizure, continued to speak to the class, offering a once-in-a-lifetime insight to students who may one day be on the forefront of epilepsy research. “It’s all about awareness,” Tim says. “People with these conditions can absolutely do amazing things.”

Kimmi agrees, saying, “And I think it's really important that they see and hear the human aspect of it.”

From their budding research into the science of epilepsy, to their integration of their personal experiences in the classroom for a new generation of scientists, and to their deep dedication to advocacy for people with disabilities—Tim and Kimmi’s journey embodies a relentless pursuit for a better world.

At the heart of their story is a powerful message: the true impact of science and education lies in its ability to transform lives, not just in theory, but in the tangible, everyday world.

If you are interested in learning more or getting involved in Tim and Kimmi’s research, reach out to tmyers@pace.edu and/or kstephens2@pace.edu.

More from Pace Magazine

Nestled in a corner of the 16th floor of the iconic 41 Park Row, a building steeped in history, the Pace Study is a hidden gem. Within its walls, the Study served as the workspace for Robert S. Pace, the second president of Pace University and son of co-founder Homer Pace. Nowadays, it's a haven for small, but significant University meetings.

Through a grant from the New York State Department of education, School of Education Professor Jennifer Pankowski is helping students with disabilities to thrive at Pace and beyond.

Through a $1.48 million grant, Pace is providing a blueprint for large-scale energy-efficient projects.