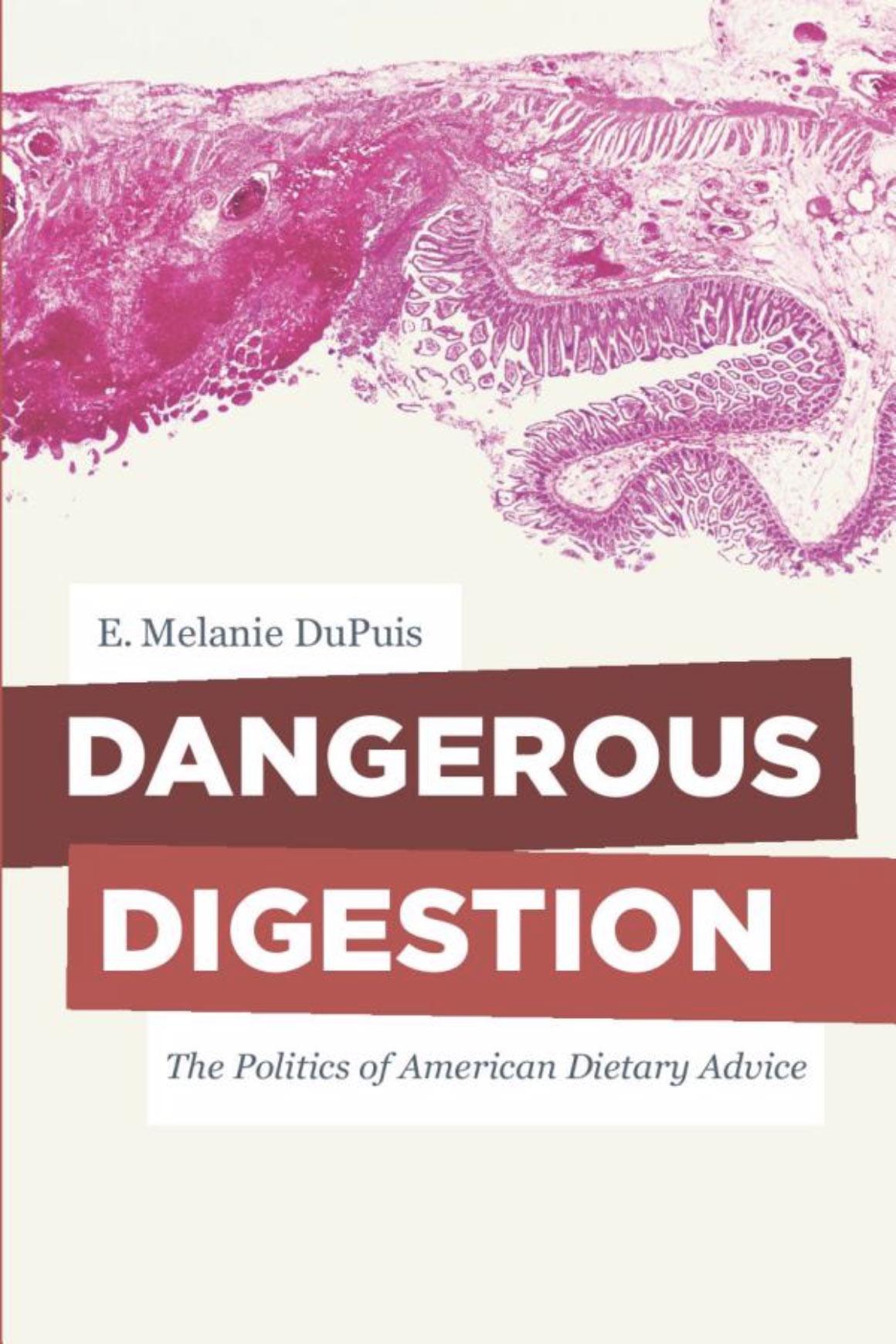

Dangerous Digestion: The Politics Of American Dietary Advice

E. Melanie Dupuis, Phd

Professor Environmental Studies And Science, Pleasantville

When did you join Dyson?

I arrived in fall of 2014. I came from the University of California, Washington Center, where I helped direct the UC internship program.

What motivates you as an educator?

The next generation is going to be making a number of tough decisions, with people who have vastly different views of the world. I hope to train students to be able to work with others to make the best of a world threatening to go bad. They will need good skills of observation and analysis as well as the ability to understand others and negotiate with them. Our Environmental Studies and Science programs are structured to provide students with these very skills.

What do you do in your spare time to relax/unwind?

I am a huge fan of live music and try to see as much of it as I humanly can. I hang out with a lot of people who were disk jockeys at their college radio station, a dying breed. We all are on the lookout for the next great musician and group, and we keep each other informed on who is touring.

What are you reading now?

Two books, a fictionalized memoir, The Emigrants, by W.G. Sebald. Many call it a “perfect book” and they are right. I’m also reading a non-fiction book, Extra Virginity, about the history of and political corruption around extra virgin olive oil. I’m working with Pace’s International Program to put together a food and biodiversity trip to Crete, and the partner I’m working with there recommended it.

What is the main plot or central theme of your book?

That two centuries of American dietary advice has not succeeded in creating healthier Americans. It succeeded instead in creating reasons to exclude some people from the rights of citizenship. There is no such thing as “pure” food and a “perfect” diet. Why are we stuck in this way of solving problems? Because we see the world through our bodies, with our food choices as a metaphor for our political choices. By rejecting the idea of pure food we can also reject purification as the solution to the world’s problems, we can figure out new ways to collaborate and probably get more done. But first we need to rethink our bodies' relationship to the world. At the end of the book I explore the current interest in fermentation and the metabiome as potential new political metaphors.

What inspired you to write this book?

At the end of my first book, Nature’s Perfect Food, I talk about how milk isn’t perfect and that we need to think beyond the idea of perfection when it comes both to food and to society as a whole. But I didn’t get a chance in that book to think that through. Looking through archives, I came upon this pamphlet written early in the 20th Century, by Samuel Gompers, called “Meat vs. Rice.” It was an argument in support of the Chinese Exclusion Acts, using diet as an excuse to keep out Chinese immigrants. After that I just jumped in. I was fortunate enough to lead a 10-week retreat where I wrote the first draft of the first chapter, which appeared in the food magazine Gastronomica.

Why is this book important in your field? What does it contribute to the current body of knowledge on its topic?

People think that my books are about food. Food is just a lens I use to understand American culture, particularly its political culture. In this case, I used food to ask why Americans think of purity as the answer to all social ills. Purity as a solution requires building strong borders between inside and outside, us and them, good and bad. It requires sorting the world into one or the other category, on either side of that border. Although that works well in hospitals and other situations that require sanitation, in politics that approach tends to create more problems than it solves.

Were students involved in any research related to your book?

Pace student, Nikita Iyengar, worked on the footnotes and was extremely helpful.

Tell me about a particularly special moment in writing this book.

As a last-minute decision, on a very busy day, I wandered into a meeting of the UC Humanities Research Institute, run by two very well-known scholars, Herman Gray and George Lipsitz. They were soliciting applications for the 10-week retreat sponsored by UCHRI. I started to lay out my ideas for a new project and before I was even finished they got very excited and told me to go write it up. I couldn’t have started the book without that retreat. It was a great help.

What is the one thing you hope readers take away from your book?

That purifying society toward one, perfect ideal isn’t the way to solve problems. There is no one perfect ideal, no one way to use the environment more sustainably, to eat healthier or to deal with any other issue. The whole idea of making people “aware” of the “right way to life” as a way to solve problems assumes that there is this one, perfect, life that, as soon as people know about it, will automatically convert them to it. Countless documentaries and education campaigns are based on this premise. Two centuries of American advice on health and longevity have been based on this as well. With a few exceptions — people do smoke less than they used to — this approach hasn’t worked. We need knowledge, but that alone is not enough.