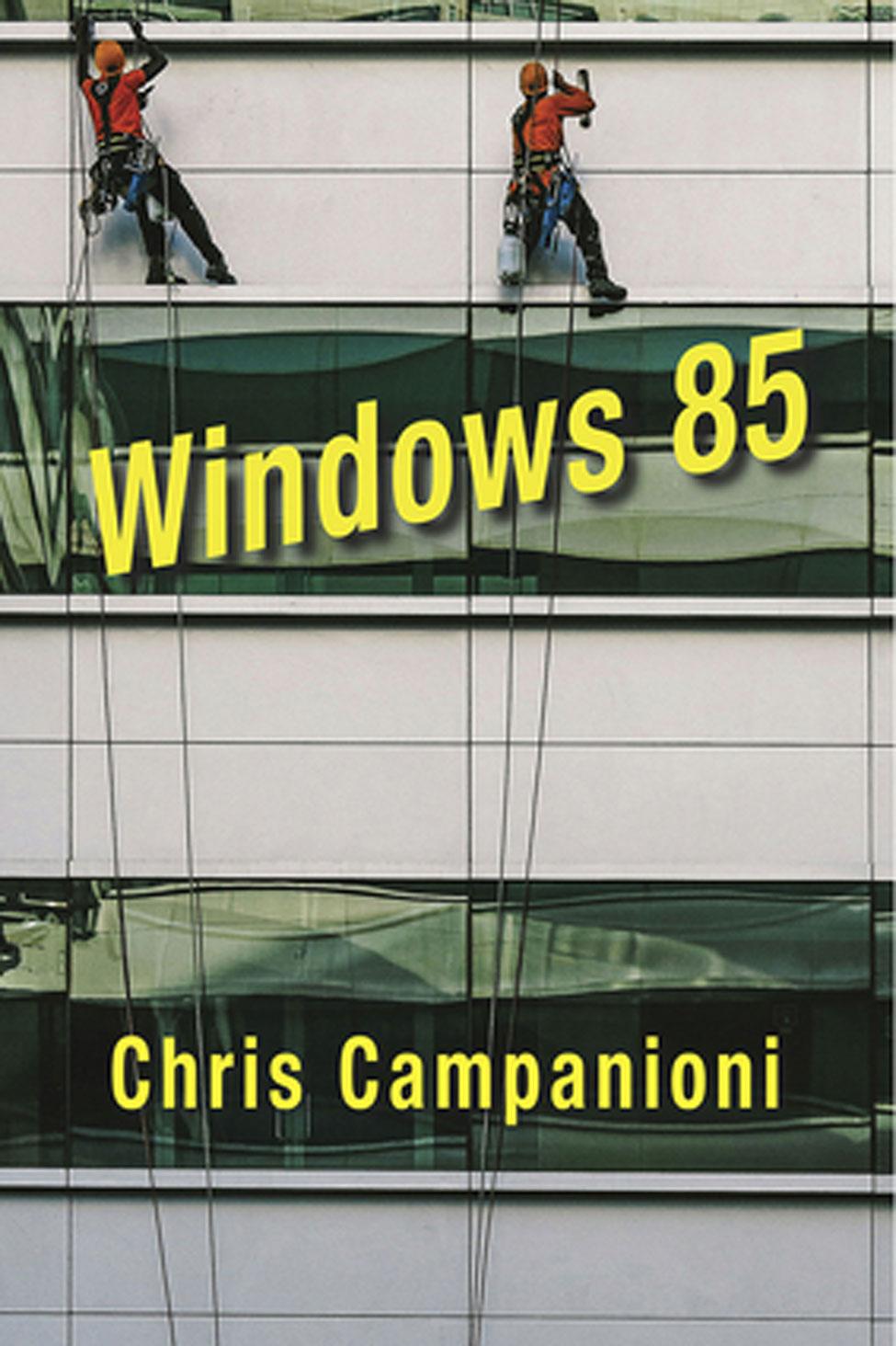

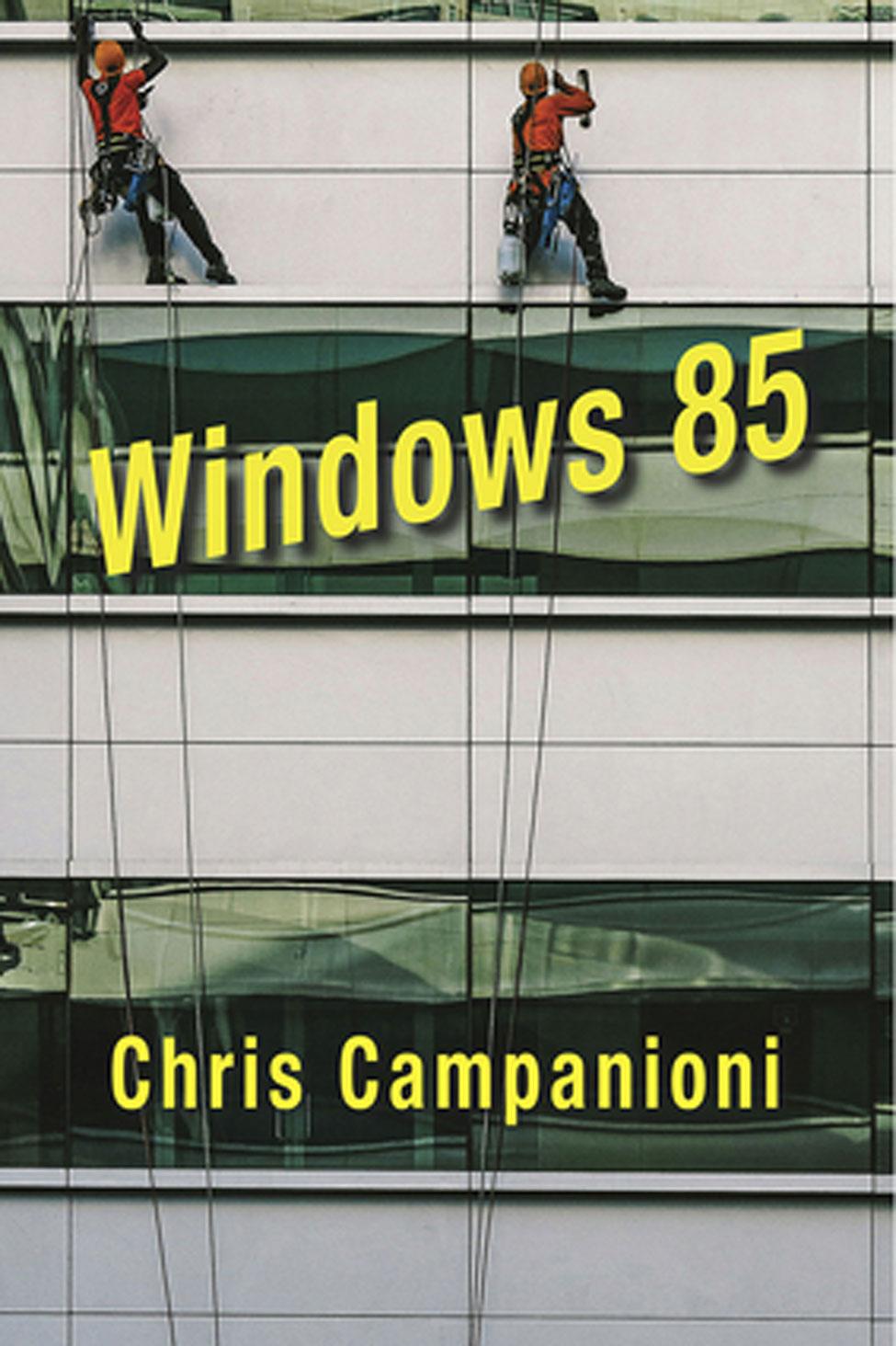

Windows 85

Christopher Campanioni, PhD

Lecturer, English

What is the central theme of your book?

The theme is identity and copresence in the age of platform capitalism and transmediation, a “networked intimacy” that I’ve engaged with for many years in my research and teaching.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’m not sure if “inspiration” is the right word, but I was drawn to the invitation and challenge to adapt my research in the field of media studies—theorizations about eyeless voyeurism and surveillant assemblages, glitch aesthetics, and the fungibility of the face—to the mode of poetry, the form and structure of lineated verse. A lot of my work is rooted in translation, through languages and through sign systems (what folks in the academy call “intermediality”); this kind of linguistic alterity, linguistic estrangement, is what I’ve been working through for many years, as both instructor and scholar, writer and translator, but also as a person. And the play with/in language that serves as, if not inspiration, then the engine for Windows 85, is where I trace my own desire to write, or at least to work with words—the exophonic urges of growing up in a home in which I was the only native English speaker, who nevertheless still feels very not fluent in English.

Why is this book important in your field? What does it contribute to the current body of knowledge on this topic?

Formally and aesthetically, as I mentioned above, I think Windows 85 provides a very specific model on how scholars might adapt their research for the public. The ideas and questions that are explored and interrogated here continue investigations of mine published in leading journals across media studies, critical theory and philosophy, and biography and autobiography studies, including Diacritics, Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, Social Identities, and Life Writing. I’m in the English department but my work is not really focused on any one field; I’d like to think that Windows 85, like my other creative publications, contributes to the growing field of critical creative writing, or what some scholars call CEW (Critical Experimental Writing), which challenges the base separation of “critical” and “creative,” but also the borders between disciplines and the material boundaries of the institution and the public.

Tell me about a particularly special moment in writing this book.

Windows 85 was written on the go, quite literally. After I defended and deposited my dissertation at The Graduate Center, I spent twelve weeks traveling through parts of Europe. So the many sites—Bologna, Berlin, Marseilles, Paris, Lisbon, et cetera—orbiting the book’s network are engrained in the fabric, but the poems themselves reference many of the unlikely encounters a person traveling for so long without pause—and lacking a stable Wi-Fi connection—might experience, like an interview conducted at a historic tennis club or a virtual poetry reading performed at a local gelateria.

What is the one thing you hope readers take away from your book?

W85 moves between settings and subject positions in a casually aggressive manner—reminds me of the way my web browser inevitably accumulates windows and tabs throughout the day—so that it becomes problematic to locate a stable subject or a single source, obscured by the poems’ proliferation of bodies and sometimes body parts. I like thinking about poetry’s power, more generally, to invite multiplicity and displacement. And I’d want readers to hold onto that, or to see the potential usefulness—the potential, even, for subversion—in moments of discrepancy, or interruption, or indeterminacy, illegibility.

What other books have you published?

My novel, Going Down, was awarded Best First Book at the International Latino Book Awards in 2014, and since then I’ve published across genres, including two hybrid nonfiction books (Death of Art and the Internet is for real, both from C&R Press), another novel named VHS (CLASH Books), a creative nonfiction called north by north/west (West Virginia University Press), a notebook now in its second edition titled A and B and Also Nothing (Unbound Edition), and a monograph on migrant subjectivity and works of art born in translation named Drift Net (Lever Press), a version of which was awarded the Calder Prize for interdisciplinary research in 2022.

Fun Facts

When did you join Dyson?

I joined Dyson in the fall of 2015—almost a decade ago—but this is my first year as a full-time instructor in the English department.

What motivates you as a teacher?

My students and their energy and curiosity. As a teacher, I think of myself as a radio player, tasked with the responsibility to tune to the different frequencies of each student, each with their own needs, their own interests, their own lives within and without the shared space of our classroom. And my favorite part about the radio is what people call “interference”: the moments when you receive a signal you hadn’t intended or could have never planned. These unforeseen and unforeseeable moments in the classroom are often the most meaningful.

What do you do in your spare time; to relax/unwind?

I wish I were better at unwinding, but I’ve always had trouble relaxing. In fact, I get most of my writing and research done when I’m at my busiest. I suppose when I’m not reading, writing, or caring for our toddler, Desi, I “unwind” by playing tennis. I fell in love with the sport again at the beginning of the pandemic, because it was one of the few activities that were still permitted during the strict sheltering guidelines. I love tennis because it’s a lot like writing, or reading for that matter. There’s such a strenuous physical challenge in tennis but it’s also so intellectual; the scenario is changing on the fly, and the only way to respond is to attend to patterns and make inferences: immediacy, guesswork, risk, vulnerability.

What are you reading right now?

I’ve just finished rereading some of my favorite novels about migration and displacement—books like Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, Cristina García’s Here in Berlin, and Dubravka Ugrešić’s Museum of Unconditional Surrender—because I’m preparing an essay for LitHub on “secondhand relations,” in part to celebrate the March launch of my next book, a novel called VHS about a narrator on the trail of his parents’ exiles who believes that he can transfer these moments, once found or filmed, onto interconnected videocassettes and thus learn something about his own past.