The Next Frontier, or an Existential Threat? How One Art Professor Approaches Generative AI

Pace University Professor of Art Will Pappenheimer is a pioneer in the digital art world, having incorporated digital media into his work since the 1990s. Pappenheimer is a founder of the Manifest.AR collective, a group of artists who manipulate the technologies provided through augmented reality to reinvent existing public art. He has traveled the world to create and showcase his work, which has been featured in renowned institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Whitney Museum of American Art, Kunstraum Walcheturm in Zurich, the Golden Thread Gallery in Belfast (ISEA 09), FILE 2005 at the SESI Art Gallery in São Paulo, and the Xi’an Academy of Art Gallery in China, among others.

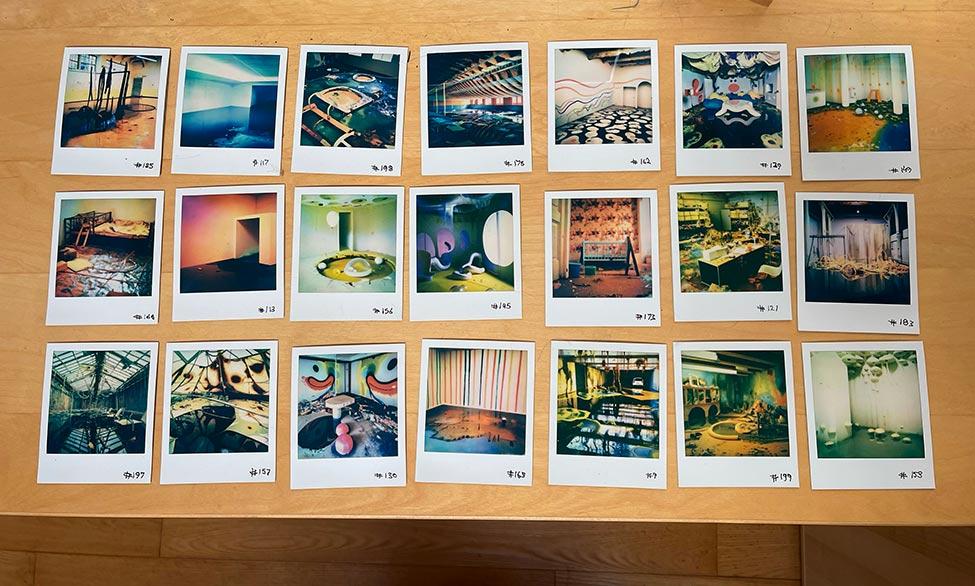

More recently, with the introduction of text-to-image generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), Pappenheimer has been experimenting with this groundbreaking medium. His latest work, shown at the Pace University Art Gallery as part of the Flux exhibit, includes video, augmented reality, and digital prints generated by AI text prompts, all investigating a devasted post-human environment.

We had the opportunity to talk with Pappenheimer about the revolutionary potential of GenAI in the art world, how this technology is changing the way he teaches and approaches his own work, ethical issues, centuries-old questions about ownership and originality, and more.

Can you describe your most recent AI-influenced work for the Pace University Art Gallery’s Flux exhibit?

The body of work that addresses AI is called Flooded and Moldy Rooms After Artists. This series of works is in the art-historical vein of artists who have done work based on previous artists, and they’re often called “after” so-and-so. “After” Rembrandt, or “After” Duchamp, for example. I created large scale prints using prompts that incorporate both a well-known artist and eccentric descriptions incorporating moldy and flooded rooms following ecological disasters.

I’m interested in the idea of a possible economic, ecological collapse, and mixing that in with a pre-existing artist’s work so you can see that artist’s aesthetics on the site of ecological disaster—focusing on the idea of the flood, and what it would leave behind.

One of the critiques of AI is that it’s using large quantities of energy through servers, and this work ties into that potential disastrous ecological future. It has a weird predictive feeling about it. One word that’s increasingly relevant in the world of digital media is the concept of “post-human”, and I’m playing off that concept.

How have you approached “creating” art through GenAI?

Going back to when this technology was first introduced, I did a bit of experimentation just as Dall-E 1 and some of the other models were beginning to operate. I found that if I created an interesting, borderline nonsensical prompt, I got very interesting results on par with artists’ works that I knew. I was very intrigued by its results.

There are a lot of complaints about AI, but I found the images it produced to be quite sophisticated. At a Pace event, I put four images on the screen—three of them were artist’s images from various collections in museums and one of them was generated by AI. No one was able to identify the AI generated image.

It’s very impressive what AI is doing, and the quality of the AI work brings up the issue of artists being concerned about their jobs and functions being replaced. I’m not making a commentary on that, I’m just saying, this art is quite good, and I think that artists are still going to be producing wonderful work.

It’s also very important to keep in mind that some of the reason AI art is good is because of the database it’s drawing from. If the database is filled with good art, made by artists, you’re going to get quite good results.

The concepts of ownership and originality are one of the major ethical concerns surrounding GenAI, especially in art. How have you approached this issue in your work?

Ideas of originality and ownership, certainly in the last few years, have been a hot button issue. It’s clear that some artists involved in more traditional art—painting, sculpture, etc.—have been uneasy about this idea that a computer can generate art.

One interesting aspect ethically and legally—as far as I know, I’m not a law professor! —is that you can’t claim ownership of an AI image because right now, because ownership/authorship by humans is defined by a human making the artwork. Since a machine arguably makes most of an AI image, that’s arguably not within the legal definition of authorship. I’m trying to get my students thinking about and discussing these issues.

That’s also why I haven’t signed the Flooded and Moldy Room prints with my name. I sign them with a very simple zero with a slash through it, pointing toward the idea that “no one person” made this image because it’s a collective image. The only thing I did was take care of the image, create the prompt, and print it carefully. On the back, I sign it with my initials saying I printed it when I printed it. The date on the image is the date that I finished with this whole process.

I am heavily involved in the creation of this art, but I’m not going to claim authorship of this whole image.

How has the introduction of text-to-image GenAI changed the way you teach?

A few years ago, when text-to-image GenAI was first introduced, I was mostly drawing a blank with students—they weren’t even using ChatGPT yet.

In a second-level digital design course, I started incorporating a GAN site—a particular form of generative AI. This site requires that you submit 30 images. It would then start to process those images together, and you’d be able to see that process. I wanted students to see this process happen. Even though GAN isn’t the only form of AI generation, it’s a way to get behind the scenes a little bit and get a sense of what’s going on when someone puts in a prompt.

More recently, there’s been a lot more AI projects, more websites, and more widespread use. A couple of my students, for example, have been using Adobe Firefly in Photoshop. I was surprised to learn how respectful they were being—they were using it for parts of an image, to complete an object they couldn’t get, or a certain area of an image to enhance or embellish.

I think the best way to deal with AI in the classroom is to talk about it, to make it a part of assignments, and dissect the nuances of how it can be used and how it affects art—I’m using it myself, after all, even if the way I’m using it is to create larger commentary.

How has the introduction of AI changed the way you approach your own work?

Because I’ve worked with digital media since the mid-90s—we’ve always been presented with these evolving media—the internet, social media, augmented reality, and so on.

With these technologies, we as artists have always looked for ways to use them—and misuse them. To jam them or do things they weren’t meant to do. I’m very used to that way of dealing with technology, and it’s still what I do. This is what I’m doing with AI, trying to get it to do something that most users of AI are not interested in, that reveals the way it really works.

As someone well-versed in the relationship between digital media and art—in what ways is AI different that the technologies that have preceded it, and i what ways is it similar? Do you feel that GenAI represents an existential threat to art?

One thing to mention in the realm of art is to understand—why would artists want to use various technologies to make their work, and what is the relationship between the artist and the machine? This is an idea that goes back to the early part of the 20th century, the Surrealists and Dada art movement, at a time when the industrial revolution was still progressing, and it was producing all types of war equipment.

Through these movements, these artists identified the machine in acting as a way that was counter to the human ego. Surrealism was the idea that the machine could better get at something that was dreamlike, as opposed to humans who are always trying to preserve their realities. And that plays a role as to why artists get interested in computer technologies and AI in particular—and has certainly been part of my interest. Using the machine to show us something that is revealing, or unconscious at a certain level.

It still requires human interaction, and we still should be very aware that at this point, AI wouldn’t be anything without humans. We’re the giant database from which AI draws upon to produce good work. There wouldn’t be good writing in Chat GPT, it’s sourcing everything from us.

As creators, we never come into work in a vacuum. We’re using history, other experiments, already accomplished science and art to build upon or tear down—we’re never coming into anything on a completely blank slate. The more originality in art is discussed, the more it’s realized that everything is based on old works. This is not to say that things aren’t done originally, that there aren’t breakthroughs and moments where people really try new things. But without this basis of pre-existing civilization—and the internet as the database—ultimately, it’s this huge and rich library that’s being accessed to create art, whether through AI or not.

More from Pace

With artificial intelligence remodeling how healthcare is researched, and delivered, Pace experts are shaping the technology—and erecting the guardrails—driving the revolution.

From helping immigrants start businesses, to breaking down barriers with AI-generated art, Pace professors are using technology to build stronger, more equitable communities.

As artificial intelligence seeps into every facet of life, Pace scholars are working to harness the technology’s potential to transform teaching and research. While the road ahead is fraught with uncertainty, these Pace experts see a fairer and safer AI-driven future.